Overcoming adversity: PhD student's journey of hope, war, and family reunion

This year was an emotional one for PhD candidate, Belay Gebregergis. Having been separated from his wife and daughter by war in Ethiopia, not knowing if they were alive for over two years, the family was finally reunited in Canada earlier this summer. Despite the stress of his family’s situation, Belay has never missed a day in the lab – his PhD studies helping him get through the trauma of temporarily losing his family.

Belay left his loved ones in Tigray, Ethiopia, to pursue a masters in Europe on the ERASMUS program. He spent a year in France and a year in Germany which gave him a very different perspective on academia. “In my home country, you don’t have much free choice. My friends and family chose that I would study pharmacy, so I did. It was normal to do such things. When I went to Europe, I realised I now had choices. I had the freedom to choose my studies, my career, how I do experiments, everything.”

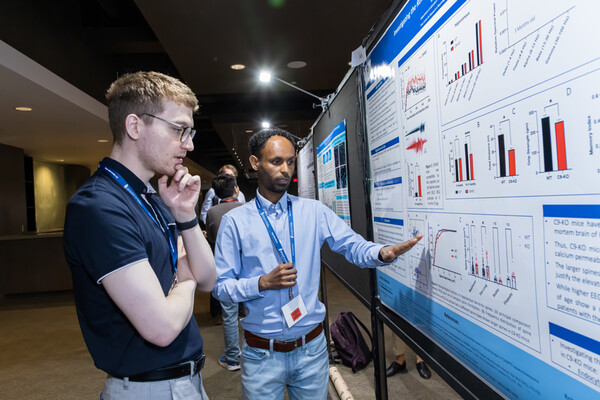

He got involved in a project on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Motor Neuron Disease, and became fascinated with the disease and neuroscience. As a result of this new interest, and the exposure to a freer culture, he decided not to return to Ethiopia. He instead secured a PhD position with leading ALS researcher, Dr. Janice Robertson, in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto, starting in Fall 2019.

“My plan was to get settled in Toronto, find suitable accommodation, then my wife and daughter would join me.” However, their visa application was cancelled when the COVID-19 pandemic caused all travel to be shut down in March 2020. “I wasn’t hugely concerned at the time,” he said, “We had already been apart for nearly three years. I thought it was temporary and, when it passed, we would resume the application and they would be here.”

He was working in the lab late one evening in November 2020 when he checked his phone and discovered the news on a whatsapp group of Ethiopian friends – civil war had broken out in Tigray. Telephone and internet were cut so he had no way of contacting his wife or family. In the months that followed, he knew his hometown was bombed, that rape and war crimes were widespread, and that his ethnic group was being targeted, but had no way to know if any of his family members were alive or where they were. “I couldn’t breathe when I first heard the news. I couldn’t sleep at night. I realised quickly that there was literally nothing I could do but hope.”

Belay turned to his supervisor for support. “Janice was amazing. She was a counsellor and a mother figure rolled into one. I would speak to her almost every day about what was happening and how I was feeling. She, and the rest of the lab, were by my side, encouraging me and motivating me. I really think the only reason I got through this was because I had my PhD project to distract me and keep me busy, and the support of my team to keep me going.”

Belay didn’t hear from any family members for over two years. “I can’t get over how resilient he was throughout that time. Despite this trauma and turmoil, he showed up every day to the lab with a smile on his face and worked so hard,” commented Janice. “Testament to this, Belay won a prestigious Brain Canada-ALS Canada Doctoral Award during this very difficult time for him, demonstrating not only his excellence in research but also his ability to persevere even under unimaginable personal stress”.

Then, out the blue in the middle of the night, he received the phone call he had been waiting for: his wife and child were safe and could get out. They started visa applications to get them to Canada as soon as possible. Janice wrote letters of support as Belay worked through the red tape. The process went faster than expected and before he knew it, his family were on their way to him. “It was so nerve-wracking when she was at the airport in Addis Ababa. It was an ethnic war, and my wife has a name that identifies her clearly as coming from Tigray. She was detained, searched, and interrogated, but thankfully, they let her on the plane.”

Belay can’t put into words the feelings he had when going to the airport to collect his family. After almost six years apart due to studies, COVID-19, and war, it was a long-awaited reunion.

“I’ve felt every emotion, from despair to relief, but this whole experience has made me stronger. We’ve been through many challenges in our lives, and this has been by far the hardest, but if we can survive this, we can get through anything.”

For now, Belay is focussing on being together with his family and healing from their trauma. Counting many friends and family among the estimated 300,000+ people killed in the war, they are grateful to be back together and safe. (Belgium’s Ghent University estimates the number of fatalities to be 300,000 - 500,000).

The future for the Gebregergis family now means “making sure we stay together” as they hope to stay in Canada and develop both their careers. The war has ended in Tigray, but political unrest and insecurity remains, so their thoughts are with others back home as they also heal. In the meantime, Belay is now focussing on his research into ALS, and the smile he wears in the lab each day is now a very happy one.

Find out more

Brain and Neuroscience research in LMP

This story showcases the Inclusive Community pillar of the LMP strategic plan.